A woman from Babar Mahal was kept in three-day police custody for investigation after she was accused of refusing to rent her house, upon learning rent seeker’s caste, to a Dalit woman.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office, Kathmandu secured her release on bail as per Article 15 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 2074 BS on Wednesday.

After being released from custody, she in her response to media persons at the police station premises admitted that she had refused tenancy upon learning the tenant’s caste. “I was shocked when the girl said she belonged to the Kami (Dalit) caste. I then told her that I’d have to consult with my family members about it,” she said.

What does the law say?

As per Article 24 (2) of the Constitution of Nepal, “In producing or distributing any goods, services or facilities, no person belonging to any particular caste or tribe shall be prevented from purchasing or acquiring such goods, services or facilities nor shall such goods, services or facilities be sold, distributed or provided only to the persons belonging to any particular caste or tribe.”

Furthermore, the Caste-Based Discrimination and Untouchability (Offence and Punishment) Act (10), Section 4, sub-section 10, “No one shall, on the ground of caste or race, exclude any member of family or prevent him or her from entering into the house or evict him or her from the house or village, or compel him or her to leave the house or village.”

What did the tenant do?

She filed a First Incident Report (FIR) with Nepal Police citing the above injustices.

What happened next?

As per the law, the government registered a case (Sarkarwadi Mudda) – Nepal government on behalf of the prospective tenant became the plaintiff versus the Homeowner.

What did Nepal Police do?

Nepal Police after finding cause for injustice detained the homeowner. Under such circumstances, the person can be kept in judicial custody for up to 25 days for investigative purposes. If a court hearing is granted before 25 days is over, the judge can allow the release of the person from judicial custody, and ask the accused to post bail.

What is judicial custody?

The difference between custody and jail being, judicial custody implies that a decision by a court is yet to be made, whereas jail means a convicted person serving a sentence mandated by court.

A politically divisive issue

It can be argued that when Education Minister Krishna Gopal Shrestha arrived at the police station in his ministerial vehicle to escort an alleged casteist homeowner, he took a public stance and sided with systemic caste-based discrimination prevalent in the country.

The Education Minister not only indulged in gross misuse of power, but also established that oppressor castes will have governmental backing to continue their oppression.

He successfully highlighted the government’s complicity towards deep-rooted casteism and the fact that Dalits as well as other marginalized communities are constantly discriminated against even by law enforcement agencies.

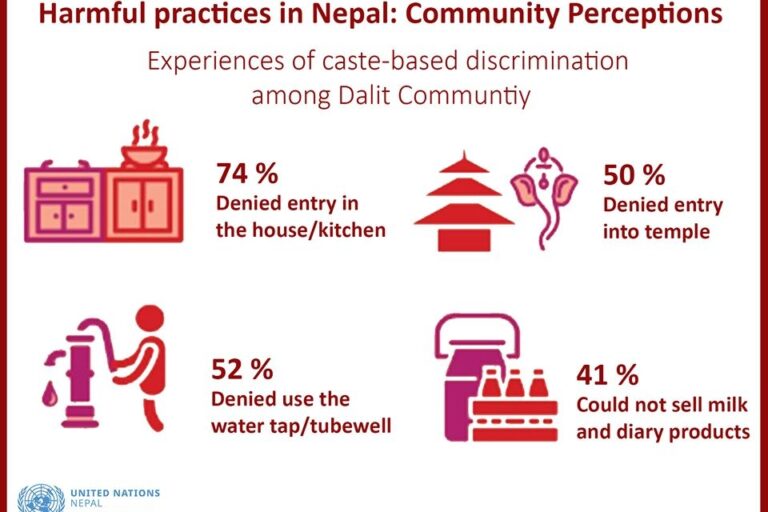

Though Nepal passed a law against caste-based discrimination and untouchability, Dalits face routine segregation and abuse and ancient biases against the so-called “lower-caste” groups make it harder for them to access education, jobs and homes.

Oppressor castes taking up space

Grave incidents often have the ability to transform into movements – usually, when they highlight, and/or relate to a larger problem within society.

Such incidents also open up a channel for dialogue between various groups – however, it is important for the dialogue to not run off-course and to deter practices which shift focus.

When media reports highlighted the tenant’s case, the incident also raised a question, “Is caste-based discrimination prevalent within Nepal’s real-estate industry? If yes, do reforms need to be introduced from the state level – along with, if possible, awareness campaign of the introduced reforms?”

As murder, violence and caste-based discrimination against Dalit communities continue unabated across the country, the issue gets space only when someone falls victim. The topic fades soon, while oppressed castes continue to suffer in silence.

Moreover, majority oppressor caste people driving the narrative and forming public psyche – online and offline — to suit themselves is a tell-tale sign of Nepalis not being ready to give up their inherent discriminatory power.

The oppression and erasure of anti-caste voices are made exponential because of the caste nexus that controls narratives on social media platforms, newsrooms, legislature – all led by dominant castes.