It is approximately 11:30 a.m. I am standing near the counter at TU Teaching Hospital, observing. An elderly man and a young girl, (presumably his granddaughter) reach out to the person behind the counter and ask for an appointment to see an ENT doctor. In a flat voice, the man behind the counter tells them the day’s quota is over, and instructs them to come back the next day. “Not after 8 a.m.”, he warns them. They obediently return.

I am tempted to reach out to them, but instead get in line. For a change, this one is short. To the same man, I ask an appointment with the ENT doctor. He says the exact same thing – his expression void of any emotion. Probing further I ask him why, he says he can only take 100 ENT patients a day.

It is afternoon – I am back at the office. I pick up my phone and reach out to three hospitals:

- Nepal Mediciti: Their doctor is done for the day, I am asked to check in the next day.

- Alka Hospital: The doctor will be visiting in the evening and I can simply walk in without an appointment.

- Grande International: The doctor will be arriving between 5 to 7 p.m. The receptionist asks me if I want to make an appointment.

I sit down to type up the article. What is the difference I ask myself? NRS 440 is the answer, and a hell lot of patience. One would think that access to healthcare and education are basic human rights, and of utmost importance, especially in a communist ruled nation, however, we cannot seem to look beyond infrastructure development. While infrastructural development is important, healthcare and education should be parallel too.

Take this case for example:

Nepal’s per capita income is USD 1048 –an average Nepali makes Rs 337 a day, Rs 500 for an appointment is out of the question. Therefore, until the public is economically empowered enough to afford private healthcare, public health institutions need to step up their game.

Government-owned and operated health institutions are in shortage in Nepal, and those available are working beyond their capacity. According to an Oxfam Report, ‘Fighting Inequality in Nepal’, ‘more than one-third of Nepal’s population does not have easy access to healthcare. Too many health facilities in Nepal lack sufficient free medicines, and there is a substantial shortage of trained medical staff. There is just one doctor for every 1,734 people in Nepal and the government estimates that they need more than 11,000 more health staff to fill the void.

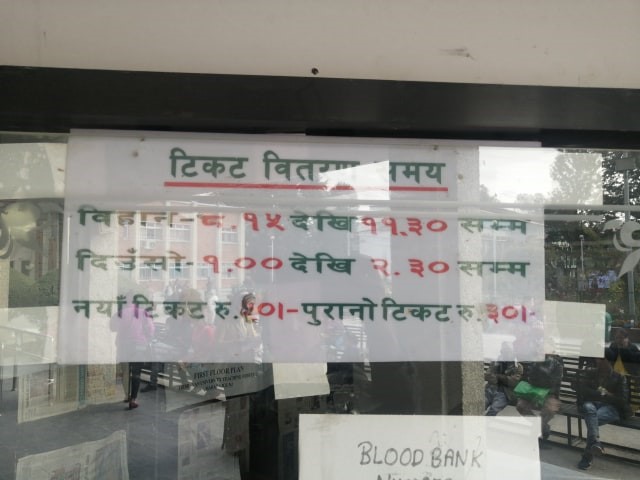

For those who arrive at a public institution, a time-consuming systemic delay awaits them. An appointment is not availed easily; one has to reach well before time to get an appointment. After getting the appointment, the waiting rooms are cramped and the attending doctors often late. The doctor may ask for other reports such as an X-ray or a urine test, and that means another line and another cramped room. To collect the report, you have to either wait for hours, or come back the next day, and yes, get in another line.

The process, for many is exhausting – many patients are non-valley residents. If they don’t have a relative’s place to take shelter in, accommodation and food costs are extra.

Non-valley residents are forced to come to Kathmandu or other metropolitan areas because their region lacks the facility, or the available facility lacks resources. For example in April, 2019, ‘eight people lost their lives owing to an unknown disease in Humla’. The affected municipality was being served by a health post which lacked the facilities to diagnose the disease – the closest hospital was a two-day walk away. Humla is a remote district in Nepal’s far-west.

Within the economically under-privileged too, women are disproportionately affected. According to the same Oxfam Report, in 2016/17 an estimated 277,344 pregnant women had unsafe deliveries and 15,760 women delivered without a skilled health attendant, putting the lives of women and children at risk. Nepal’s maternal mortality ratio is 239 per 100,000 live births and the infant mortality rate is 32 per 1,000 live births.

The government needs to pay attention towards the issue – especially after arriving in power with the promise of change and an end to inequality at its core. Access to healthcare and proper education are key proponents which drive a nation out of poverty – more facilities need to be built, doctors/health staff should be encouraged to fill the vacant posts in health facilities.

Public health facilities should be at par with private facilities, only then will we see price-based competition within the private sector too.