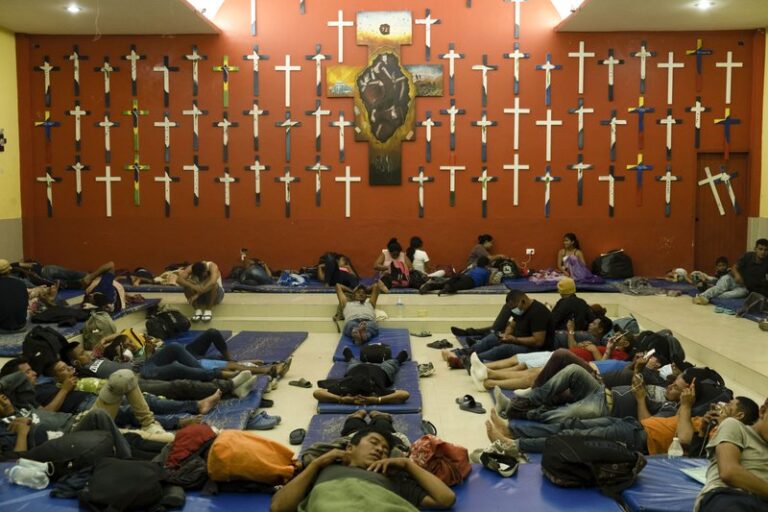

(AP) — In the first Mexican shelter reached by migrants after trekking through the Guatemalan jungle, some 150 migrants are sleeping in its dormitories and another 150 lie on thin mattresses spread across the floor of its chapel.

Only six weeks into the year, the shelter known as “The 72” has hosted nearly 1,500 migrants, compared to 3,000 all of last year. It has halved its dormitory space due to the pandemic. That wasn’t a problem last year because few migrants arrived, but this year it’s been overwhelmed.

“We have a tremendous flow and there isn’t capacity,” said Gabriel Romero, the priest who runs the shelter in Tenosique, a town in southern Tabasco state. “The situation could get out of control. We need a dialogue with all of the authorities before this becomes chaos.” In particular, he would like the government to assist with migrants who camp outside while they are full.

Latin America’s migrants — from the Caribbean, South America and Central America — are on the move again. After a year of pandemic-induced paralysis, those in daily contact with migrants believe the flow north could return to the high levels seen in late 2018 and early 2019. The difference is that it would happen during a pandemic.

The protective health measures imposed to slow the spread of COVID-19, including drastically reduced bedspace at shelters along the route, mean fewer safe spaces for migrants in transit.

“The flow is increasing and the problem is there’s less capacity than before to meet their needs” because of the pandemic, said Sergio Martin, head of the nongovernment aid group Doctors Without Borders in Mexico.

Some shelters remain closed by local health authorities and almost all have had to reduce the number of migrants they can assist. Applications for visas, asylum or any other official paperwork are delayed by the government’s reduced capacity due to the pandemic to process them.

“This is not a post-COVID migration; it is a migration in the middle of the pandemic, making it all the more vulnerable,” said Ruben Figueroa, an activist with the Mesoamerican Migrant Movement.

Some migrants have expressed hope of a friendlier reception from the new U.S. administration or started moving when some borders were reopened. Others are being driven by two major hurricanes that ravaged Central America in November and desperation deepened by the economic impact of the pandemic.

Olga Rodríguez, 27, had been walking for a month since leaving Honduras with her husband and four children, aged 3 to 8, after Hurricane Eta flooded the street vendors’ house. They arrived in Mexico and applied for asylum, but told it would take six months. Forced to sleep in the street, they changed plans.