Almost every time I write the word ‘patriarchy’, people think I am attacking all men in general. Therefore, to those who believe an attack on patriarchy is an attack on all men, it is essential for me to reiterate the reference to patriarchy here is as of a social structure – the analysis of power-distribution within a society (and the abuse of it).

Patriarchs can be from any gender, it does not have to necessarily be the violent portrayal of a male. Similarly, the ones affected by patriarchy can be from any gender too, and typically extends to family members within a household. However, the take away from it as being a social structure is how does it affect children within a home? Does it teach us “not to question authority when the patriarch is in the wrong?” And does that eventually spill outside our homes too? Are our political leaders are patriarchs because perhaps they were raised in a patriarchal society? Lastly, if our current leaders learnt from their predecessors, are our future leaders learning the same too? And is better political accountability to the people in sight?

To understand this argument, perhaps this short fictional story would be better:

Once upon a time lived two brothers – circumstantially both were raised differently. One navigated political rallies, served jail time; the other took a much more drastic approach – including the death of several innocents. Both believed they were working for a reformed society.

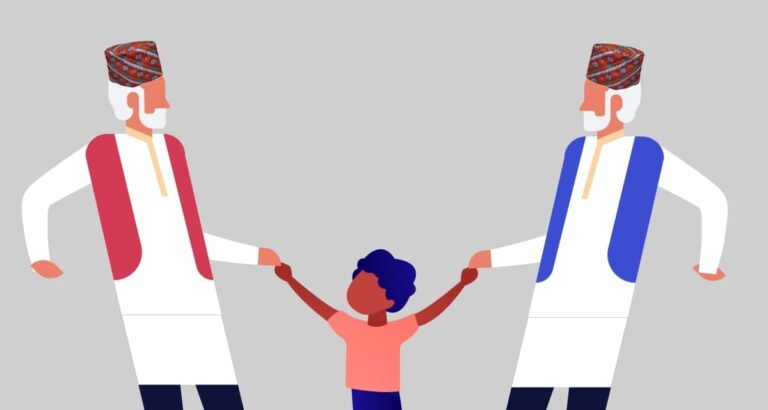

Despite their differences while growing up, somehow in their later years, they reconnect – it is unclear if either has ulterior motives when they are joining hands. It is also important to note that both these heads have married and raised children – let’s say their children are the people of Nepal.

These poor children, who have already lived through a horrific childhood (the Nepalese Civil War), are happy some stability (political) has finally arrived – therefore, they accept the union.

It is important to note that these children were not consulted before the two brothers united – and are all of sudden put in the same home and asked to live together in peace – without questioning the reasons for the unity.

Now, the brothers begin to bicker – both want the patriarchal seat (the chair of the Prime Minister). Initially, the fight is limited to the two brothers, and a few close elders, but eventually, because reconciliation isn’t in sight, it spills on to the children.

And one day, with a snap of a finger, the two families separate – children of both families, thrust into confusion, join the blame game.

“Your father has undermined democracy”, says the child of the younger brother.

“Your father has killed people for power”, says the child of the elder brother.

Poor children, raised in a system where they are barred from questioning their own authoritative figure – therefore have to resort to accusations.

The fight however does not end there – both fathers take turns in showing off their power, completely ignoring the effects of their decisions.

One day, family members of the younger brother decided to protest the unilateral decision taken by the elder brother – they gather around the main gate effectively blocking the way. Children of both the brothers, many who had to leave the home on that day were faced with difficulties – but they silently accept their cursed fate.

The younger brother is still not satisfied. He wants to do something more concrete – then prevents family members from stepping outside their homes for a day, and instructs a few loyalists to enforce his decision. For his part, he takes a tour in his car around the neighbourhood, and enjoys the spectacle.

Yet again, members of both families were affected.

Then came the next day, the elder brother, who had been accusing the younger brother of inconveniencing other family members decides to put himself out there –just to see the kind of support he has.

A crowd gathers, and placing himself in the backdrop of an erstwhile patriarch – Nepal’s monarch, he appeals directly to the public. Enjoying the spectacle, he declares himself the protector of the family – just like monarchs would do in the past.

Then comes today, there is another mass stage planned, and I, one of the member of the family, is highly inconvenienced, wondering how many hurdles I will have to face as I make my way around town to complete my tasks for the day.

All unwarranted.

All because the two patriarchs cannot come upon an agreement with each other – lacking complete accountability towards their family members.