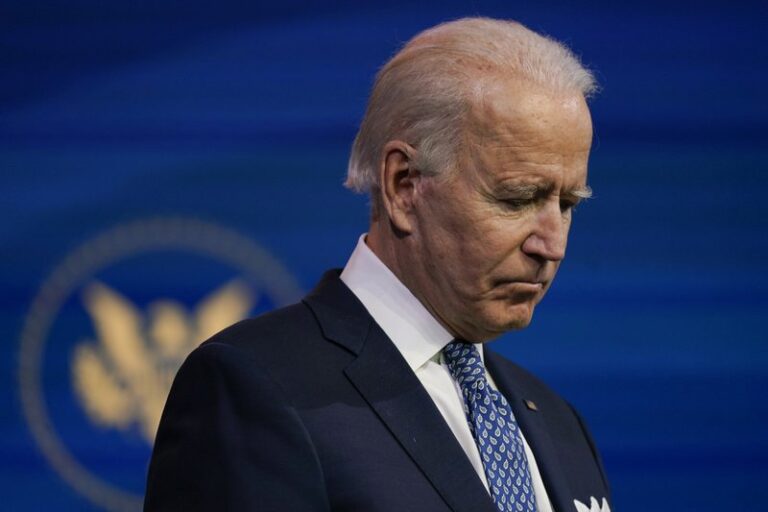

(AP) — For President-elect Joe Biden, Washington’s year-end burst of deal-making brought renewed hope for a productive, successful first 100 days in office.

The city’s fever broke, at least momentarily, as longtime combatants finally forged a COVID-19 relief deal that carried with it dozens of smaller bills, offering proof that Capitol Hill’s damaged systems and norms can still produce meaningful legislation — at least when backed up against the wall.

Most of Biden’s 36 years in the Senate came in an era when Washington functioned far better. As president he will be seeking to restore at least the veneer of good faith and bipartisanship that defined those times and cast aside the divisions of the tea party era and four years of President Donald Trump.

In that context, the year-end deal — powered by the imperative to deliver pandemic relief to a struggling nation — is a good omen. At the end, it featured good-faith negotiation among Capitol Hill’s skilled but battling leaders as well as a productive role for moderates and pragmatists in both parties whose efforts are often brushed aside.

“We have our first hint and glimpse of bipartisanship,” Biden said Tuesday. “In this election, the American people made it clear they want us to reach across the aisle and work together.”

The demand for bipartisanship is a common refrain that often comes as a throwaway line from Washington pols who have little experience in delivering it. But Biden has made it the centerpiece of his transition message — and he has a track record in the Senate and in the Obama administration of following through.

He also has no choice. The election delivered Democrats the narrowest House majority of the modern age and a narrowly divided Senate that demands bipartisanship, even if Democrats win control of a 50-50 chamber after next month’s twin Georgia runoff elections.

Biden said there is much more work to do and spoke optimistically of lawmakers coming together again in January or February to pass another package — and the template for success is there.

There are few measures of success greater than a big, bipartisan vote. By that metric, the 5,593-page, end-of-session behemoth — combining a $900 billion COVID-19 relief deal, a $1.4 trillion catchall spending bill, and dozens of late-session add-ons — was a smash hit. The 92-6 Senate vote and a pair of lopsided House tallies on the final bill came after months of indecision and deadlock were replaced with frenzied deal-cutting and compromise.

Yet there are those in Biden’s party deeply skeptical that bipartisanship can take root in such a starkly polarized country. Republicans are certain to feel the pull of their far-right flank in the coming era, shifting the party to a debt-and-deficits focus that may well be incompatible with much of Biden’s agenda.

And then there’s the Capitol itself. The pain-inducing process that led to the final virus package offered almost daily lessons in Congress’ capacity for dysfunction and wheel-spinning. And enormous power remains concentrated in the hands of only a few leaders.

Top Republicans, like Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., who will be a critical power broker during Biden’s first two years in office, credited Biden with getting Democratic leaders such as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., to accept a bill that was smaller than those she rejected in the summer and fall.

“The new president was helpful in suggesting that we ought to go ahead now and I think that may have had an impact on the speaker,” McConnell told reporters Monday.

Biden and McConnell have a long relationship and worked out several deals on taxes and spending during President Barack Obama’s first term. The polarization of the parties and the scorched-earth politics of the past decade won’t make that success easy to replicate, but Biden is all-in.

“They know I level with them,” Biden said of Republicans. “They know I never mislead. They know I tell them the truth, and they know I don’t go out of my way to try to embarrass.”

Bipartisanship and deals with McConnell were hardly the message voiced by most Democrats during a campaign in which liberals schemed to get rid of the Senate filibuster to power through their agenda.

But when Pelosi pulled back from demands for more than $2 trillion in COVID-19 relief earlier this month, there was little public backlash from arch progressives. Instead, Democrat after Democrat issued praise for the legislation even though it offered less direct aid to struggling people than they wanted.

The optimistic take is that COVID-19 relief, with its near-universal support in Congress, amounts to training wheels for a post-Trump Washington to find its way. While topics like immigration and taxes may be too tough to tackle, there’s genuine hope in areas like infrastructure.

Pelosi is Biden’s most powerful asset but she will have her hands full managing the smallest House majority of modern times. Her caucus increasingly tilts to the left and it sustained deep losses in swing districts and Trump country in the fall. But there’s no sense, it seems, in catering to the left under the looming balance of power — and a mid-term election in 2022 that will determine whether Biden’s Democrats lose control of the House.

Pelosi and McConnell have a strained relationship, but when their interests align and when they work in tandem, they are an unstoppable force. The pending new agreement started out as one to work out the annual appropriations bills. It quickly became clear that momentum could be sustained as senior lawmakers were given opportunities to find agreement on taxes, education, energy, and appropriations.

The skill is there. Finding the will and the way is the challenge.

Democratic lobbyist Steve Elmendorf said Biden and his team are going to be highly engaged and that gives him reason for optimism.

“These people are obviously dysfunctional and have some challenging relationships,” he said of Trump and his team and allies. “The fact that it took so long to get them in a room is everybody’s fault. Well, Joe Biden’s not going to let that happen.”

Washington, however, rarely rewards those who suspend their cynicism. Democrats who give grudging respect to McConnell say the best hope for bipartisanship may be his desire to do what’s best for the GOP’s hopes to hold the Senate — just as they detect the politics of the Georgia runoff races as a reason for McConnell’s flexibility now on pandemic relief.

“We’re accustomed to each other but he’s got a pretty big job,” McConnell said of Biden. “So we’ll see how that works out.”