(AP) — The weekend oil leak along the Southern California coast happened not far from the site of the catastrophe more than a generation ago that helped give rise to the modern environmental movement itself: the 1969 Santa Barbara spill.

That still ranks in the top tier of human-caused disasters in the United States and is the nation’s third-largest oil spill, behind only the 2010 Deepwater Horizon and 1989 Exxon Valdez calamities.

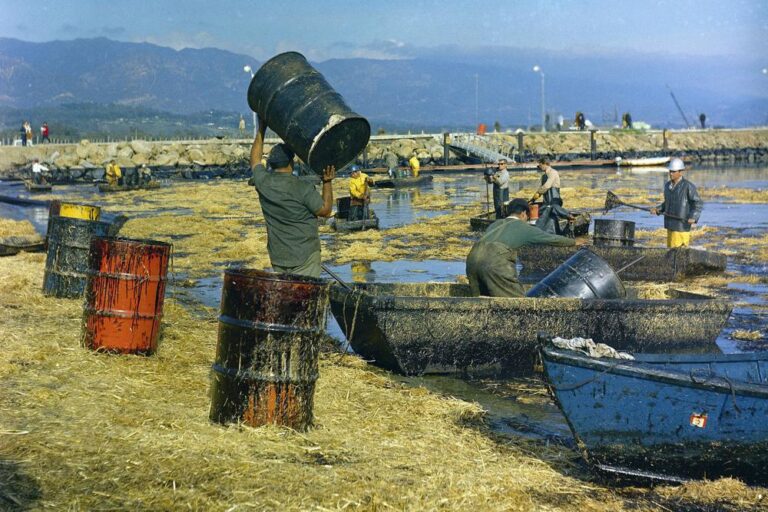

During a 10-day period in early 1969, between about 3.5 million and 4.2 million gallons of crude spilled into the Santa Barbara Channel after a blowout six miles offshore on a Union Oil drilling platform. The disaster area was about 115 miles from the site of the 126,000-gallon spill over the weekend that fouled Huntington Beach, a celebrated surfing spot.

The Union Oil rig had been controversial since its inception, but local California communities hadn’t been given any voice in decisions about drilling in federal waters. And corners were cut during the construction process: Regulations called for protective steel casing to extend at least 300 feet below the ocean floor, but the company obtained a waiver allowing it to install only 239 feet of casing.

In the aftermath of the spill, thousands of oil-coated birds perished and photos of the carnage on beaches were widely circulated in newspapers and magazines.

President Richard Nixon visited the site in March 1969 and told reporters, “It is sad that it was necessary that Santa Barbara should be the example that had to bring it to the attention of the American people.”

That example — of communities left out of crucial decisions and corners cut to save time or money for large companies — garnered national attention and caused outrage. It added momentum to the movement to organize the first Earth Day the next year.

Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson, an early environmentalist, visited the Santa Barbara oil spill site and later said it inspired him to organize “a nationwide teach-in on the environment.”

The oil spill was not the only U.S. environmental crisis in the 1960s. The links between rampant overuse of the pesticide DDT and damaged ecosystems — including the dwindling population of bald eagles — were the subject of Rachel Carson’s seminal 1962 book, “ Silent Spring.”

A raft of far-reaching federal environmental legislation was enacted in the early 1970s, including the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970) and the passage of the Clean Air Act (1970) and Clean Water Act (1972).

“It’s frustrating that spills like this keep happening,” said Damon Nagami, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, as he walked along cordoned-off areas of Huntington Beach. “I grew up near here, so this feels really personal.”

“These are entirely preventable catastrophes,” he said, though he added that managing offshore drilling is complex because “there are lots of regulatory bodies with overlapping responsibilities, depending on whether the activity is happening in federal waters, state waters or international waters.”

Oil spills damage coastal ecosystems, marine life and, if the oil-laden water moves into storm drainage systems, local communities. “Once the oil gets into an ecosystem, it’s hard to get out,” Nagami said. “The impacts are felt for years, for decades.”

Don Anair, a research and deputy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, said oil spills are “a very visible image of our reliance on fossil fuels.”

“We should be doing all we can to make sure the infrastructure is as safe as possible, but even that won’t fully eliminate the risk of oil spills,” he said. “The longer-term solution here has to be transitioning to using other sources of energy” to power our vehicles.

According to the EPA, the transportation sector is the country’s largest primary contributor to climate change, responsible for around 29% of greenhouse gas emissions.