(AP) — Just 19 years after devastating defeat in World War II, the 1964 Tokyo Olympics showcased the reemergence of an innovative country that was showing off bullet trains, miniature transistor radios, and a restored reputation.

Japan’s resiliency is on display again, attempting to stage the postponed 2020 Tokyo Olympics in the midst of a once-in-a century pandemic. The challenge is different, and this time there is widespread public opposition that has divided the country over the health hazards with nagging questions about who benefits from staging the Games.

Roy Tomizawa, who documented the ’64 Olympics in a recent book, described those distant Games 57 years ago as the “Inclusion Games” in an email to The Associated Press.

He called the attempt this time the “Exclusion Games.” But he offered some hope.

“Whether you agree or disagree with the Japanese government, the Games are going ahead in the face of significant risk,” Tomizawa said. But he said these Games might also be turned into “Inclusion Games.”

“With a high degree of difficulty,” he added.

“Organizing an Olympics and Paralympics during this pandemic is like Simone Biles executing a Yurchenko Double Pike, a vault so difficult no other female gymnast wants to do it. Biles can. Maybe Japan can, too,” Tomizawa said.

Tomizawa’s book is titled: “ 1964 — The Greatest Year in the History of Japan: How the Tokyo Olympics Symbolized Japan’s Miraculous Rise from the Ashes. ” It came out last year, just months before the postponed Olympics were to open.

Tomizawa writes in the book about the massive effort to be ready in ’64:

“Police were taking pickpockets off the streets and ensuring bars in Tokyo were complying with directives to close down early. … In fact, every man, woman, and child in Japan was getting ready to welcome the world to their country believing it was their civic duty to ensure that foreigners who came to town were not deprived of any necessity or assistance.”

This was the year that Cassius Clay won the heavyweight championship and became Muhammad Ali. It was when Roy Emerson of Australia and Maria Bueno of Brazil took the titles at Wimbledon, when Arnold Palmer claimed his fourth and final Masters, and when the Beatles arrived on a Pan Am flight from London to play their first concert in the United States.

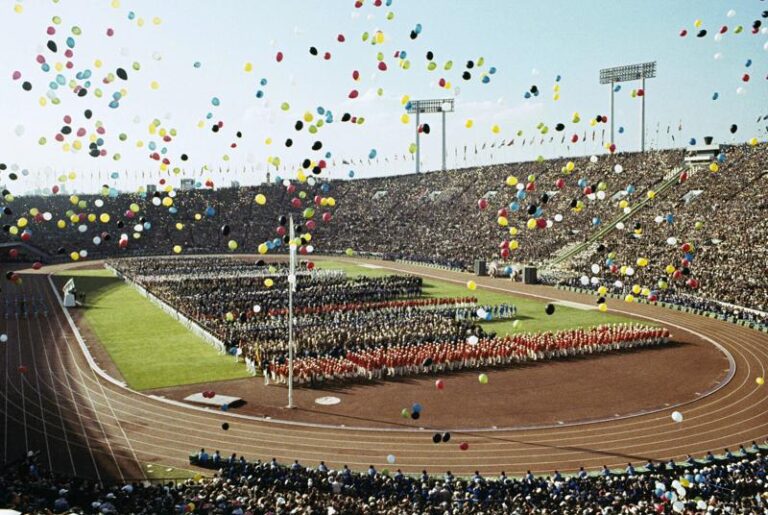

And it was later that same year in Tokyo when Yoshinori Sakai — born on Aug. 6, 1945, in Hiroshima, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on the city — ignited the cauldron in the national stadium to open the 18th Olympic Games.

Tomizawa grew up in New York, and his father, Tom, a second-generation Japanese-American, was an editor who worked for the television network NBC at the Olympics in Tokyo — the first to be shown internationally using communication satellites.

The family connection and curiosity got Tomizawa looking for a history in English of those 1964 Games. He couldn’t find one, so he wrote his own.

Tomizawa, who has worked for 20 years in Japan, interviewed 70 Olympians from 16 nations. Some were famous at the time: Australian swimmer Dawn Fraser or American 10,000-meter gold-medalist Billy Mills.

Some made other history, like Bulgarian teammates Nikolai Prodanov and Diana Yorgova, who were married in Tokyo during the Olympics. It was billed as the first Olympic wedding and featured a Shinto priest, sake, traditional Bulgarian dances, and an interpreter to explain what was going on.

He said his favorite interview was with Jerry Shipp, a shooting guard on the American gold-medal winning basketball team coached by Hank Iba. It lasted for several hours with Shipp recounting a tough childhood growing up in an Oklahoma orphanage.

Shipp led the Americans in scoring ahead of Bill Bradley on a team that also included Larry Brown and Walt Hazzard. In addition to Shipp, Tomizawa also interviewed Jeff Mullins, Mel Counts and Luke Jackson.

“I think the Olympians tell more of the story of the Games themselves and their reaction to what they saw of Japan,” Tomizawa said. “Some had been to Japan in ’50s and ’60s. I think everyone was surprised and shocked when they arrived in Japan thinking it would be a backward economy.”

They were also taken aback by the nature of the Japanese.

“For the Canadians, the Australians, the Americans, the Brits — it was the brutal enemy,” Tomizawa said. “When they came, they were welcomed and given such help and support and cheering. It was a surprise to all of them.”

They also found what Tomizawa called “operational excellence,” convincing doubters about the country’s capabilities. The current Tokyo organizers will need that resiliency, although just getting through these Olympics is sure to be portrayed as a success no matter the details and the financial costs.

Japan is officially spending $15.4 billion on the Olympics, but government auditors say the costs are much higher. All but $6.7 billion is public money.

The International Olympic Committee chips in about $1.5 billion, and some of this is payment-in-kind rather than cash. Its payoff is the $3 billion to $4 billion it earns in broadcasts rights, much of which would be lost with a cancellation.

“Now with the world struggling to combat the coronavirus, there is a question whether Japan can get ready for a global competition within its borders,” Tomizawa said by email. ”If it can, then Tokyo 2020 is an opportunity for Japan to show the world how resilient this nation, and the world can be. Just bringing athletes from around the globe to compete in Japan will be a monumental achievement.”